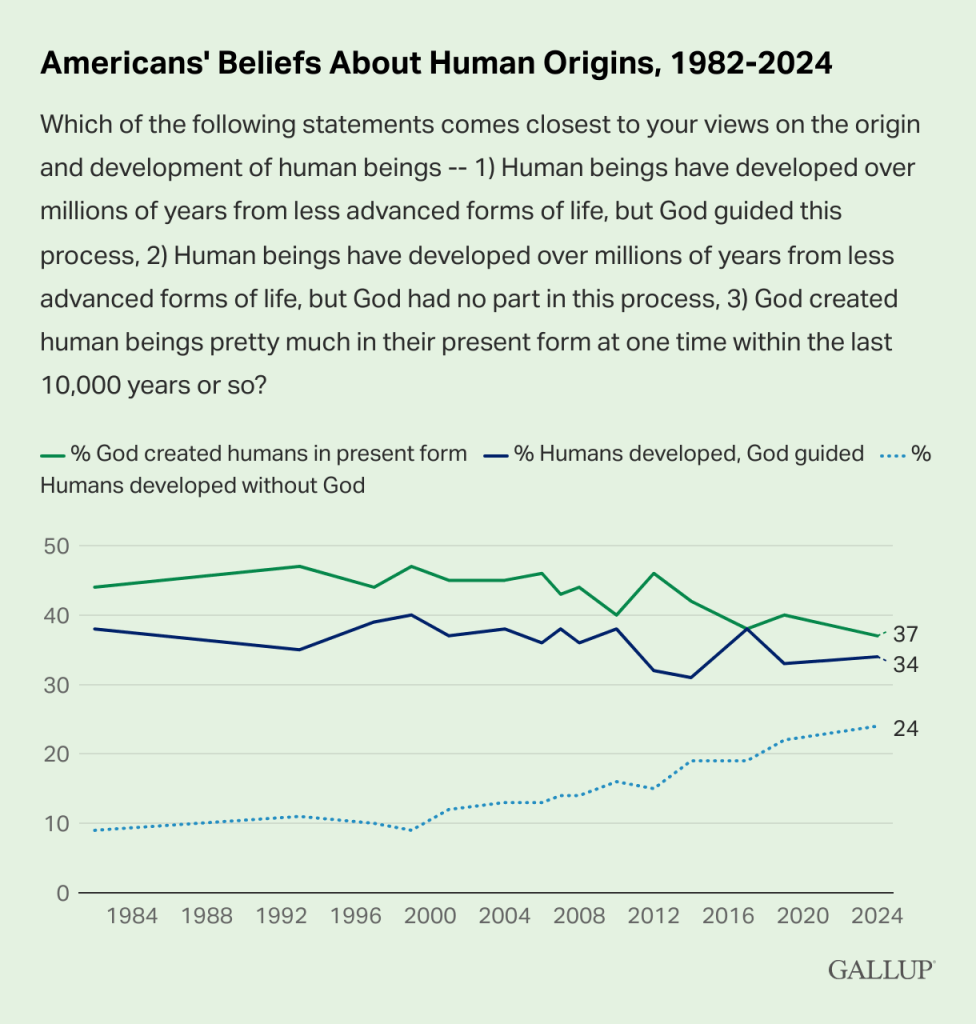

Recent surveys suggest that a significant portion of the American public remains unconvinced by evolution. Around one-third of respondents report believing that humans originated in their present form within the last 10,000 years, while fewer than a quarter accept that humans evolved without supernatural involvement. In my opinion, these numbers highlight a gap in exposure, explanation, and trust.

The goal of this article is to clearly present the evidence for evolution in a way that is accessible and grounded in observation. Whether one chooses to incorporate God into that story is a personal decision. At the very least, this article aims to establish common ground on a simpler point: life on Earth has changed over time, and those changes follow understandable, testable patterns.

What is Evolution?

Evolution refers to changes in the genetic characteristics of populations across successive generations. These changes are not guided by foresight or intention, but arise through variation, inheritance, and differential survival.

Natural selection is the process by which traits that enhance survival or reproduction tend to become more common over time. First described by Charles Darwin, it offers a mechanism for how evolutionary change occurs—not by sudden leaps, but through countless small differences accumulating across generations.

Fact or Theory

A common question often arises: “If evolution is real, why is it called a theory?”

In science, a fact is an observation—something directly measured or recorded. Evolution qualifies as a fact in this sense: populations of organisms demonstrably change over generations. This has been observed in nature, in laboratories, and in the genetic record itself.

A theory, by contrast, is not a guess. It is a well-tested explanatory framework that accounts for a large body of facts. Natural selection is such a theory—it explains how evolutionary change happens. Far from weakening the case for evolution, the theory of natural selection strengthens it by unifying evidence from fossils, anatomy, genetics, geography, and direct observation under a single, coherent explanation.

From the Beginning of Time to Life on Earth

13.8 billion years ago space and time as we know it burst into existence. The universe rapidly expanded and cooled, allowing the simplest elements—mainly hydrogen and helium—to form. Over billions of years, gravity pulled this material together into stars, where intense heat and pressure produced heavier elements such as carbon, oxygen, and iron.

When large stars reached the end of their lives and exploded, these elements were released back into space, becoming part of the raw material for new stars and planets. About 4.6 billion years ago, one such cloud collapsed to form the Sun and a surrounding disk of gas and dust. Within this disk, rocky planets slowly took shape, including Earth, which cooled enough to develop a solid surface, liquid water, and an environment rich in chemical activity.2

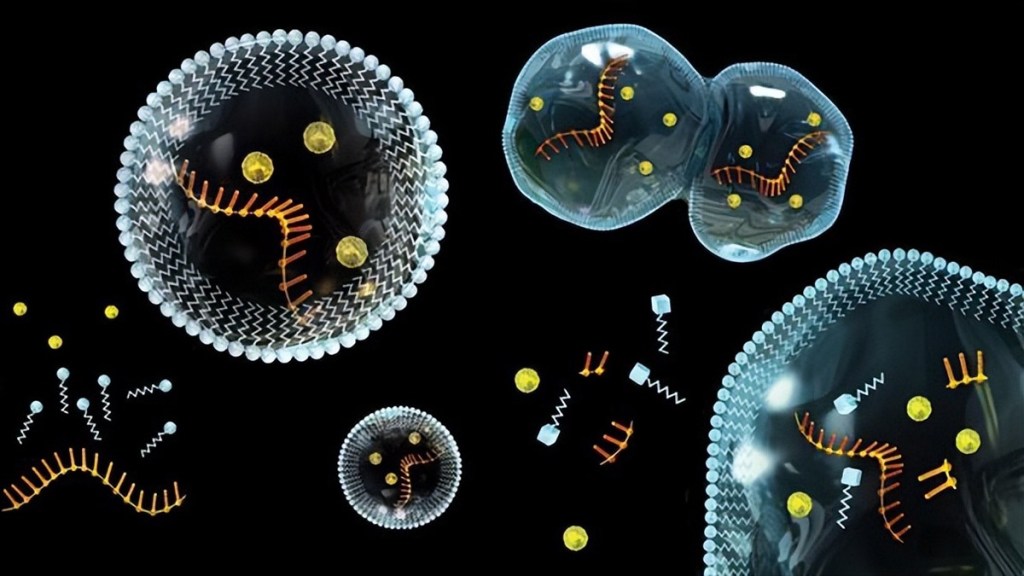

On the early Earth, simple chemicals were constantly interacting, breaking apart, and recombining under the influence of heat, radiation, and electrical activity. Most of these reactions led nowhere, but over time some produced molecules with a unique property: they could create near-perfect copies of themselves.

This marked a fundamental shift: once replication with variation existed, natural selection could begin to operate even in the absence of cells or genes in the modern sense. Molecules that persisted longer or copied themselves more efficiently became more common, while less effective variants disappeared.

These early replicators represent the point at which chemistry gave way to evolution, setting in motion the long, cumulative process that would eventually give rise to all life on Earth.3

The earliest evidence of life on Earth appeared around 3.8 billion years ago, in the form of single-celled organisms. These early life forms were simple, microscopic, and lived in a world without oxygen. For more than a billion years, life on Earth remained exclusively single-celled, gradually refining the basic processes of metabolism and replication.4

A major turning point occurred with the rise of photosynthetic organisms and the Great Oxygenation Event, beginning around 2.4 billion years ago, which permanently altered Earth’s environment. With these changes, life was able to support greater complexity. Cells became more elaborate, forming long-term partnerships. Eventually, groups of cells began cooperating as multicellular organisms.5

Around 540 million years ago, life entered the Cambrian Explosion, a period marked by the rapid appearance of diverse and complex animals in the fossil record, including the first animals with back bones—vertebrates. Over time, vertebrates diversified into fish, and some later evolved four limbs capable of supporting life on land. These first tetrapods, appearing around 370 million years ago, gave rise to amphibians and later reptiles. Reptiles would eventually dominate Earth’s ecosystems during the age of the dinosaurs, which persisted for over 160 million years.6

Unfortunately for the dinosaurs, about 66 million years ago an asteroid struck Earth near what is now Mexico, triggering a mass extinction event. This ended the age of non-avian dinosaurs allowing even further diversification of mammals.

Over tens of millions of years, this diversification produced an extraordinary range of forms, eventually leading to the emergence of anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens, in Africa around 250,000 years ago, bringing the evolutionary story to the present day.7

Multiple Lines of Evidence for Evolution

With this timeline in place, we can now turn to the evidence that supports evolution. What follows is not an exhaustive list, but a set of well-established observations that have been examined from many angles.

Science is often misunderstood as an attempt to prove ideas correct, when in fact it works in the opposite direction. Scientists begin with explanations and then actively look for ways they might be wrong. Hypotheses are tested, challenged, and shared so that others can attempt to break them. The ideas that endure are not accepted because they are convenient or comforting, but because repeated efforts to disprove them have failed. It is in this way—through skepticism, testing, and correction—that scientific knowledge slowly earns its reliability.

The evidence for evolution emerges from this process across many independent fields, from the fossil record and the structure of living bodies to the shared language of DNA, the geographic distribution of life, and evolution observed in real time.

The Fossil Record: Life Written in Stone

Fossils provide a chronological record of life on Earth, preserving evidence of organisms that lived millions of years ago and revealing a broad progression from simpler forms to more complex ones. While fossilization itself is rare, the fossils that do form are not scattered randomly through time. Instead, they appear in a consistent and predictable order that reflects the gradual change of life over time.

The ages of fossils can be determined with a high degree of confidence using well-established dating techniques. For ancient materials, scientists rely on radiometric dating, which measures the predictable decay of radioactive isotopes found in surrounding rock layers. Because these decay rates are constant and independently measurable, they allow fossils to be dated with relatively small margins of error, often within a few percent. These methods are routinely cross-checked using different isotope pairs and geological evidence, producing consistent results across independent lines of inquiry.8

Despite fossilization capturing only a small sample of past life, the fossil record contains many clear examples of transitional forms—organisms that display features of both ancestral and descendant groups. Fossils such as Tiktaalik, which shows a combination of fish and early tetrapod characteristics, and Archaeopteryx, which exhibits traits linking dinosaurs and birds, demonstrate how major evolutionary changes occurred through gradual modification rather than sudden leaps.

Perhaps most compelling is that the fossil record consistently matches the predictions made by evolutionary theory. More complex organisms never appear before their simpler ancestors, and major groups emerge in a well-ordered sequence over time. Despite more than a century of intensive searching, no fossil has been documented that fundamentally contradicts this order. This non-random pattern provides strong evidence that life on Earth has changed gradually and systematically over billions of years, exactly as evolution predicts.

Comparative Anatomy: Shared Designs and Shared Origins

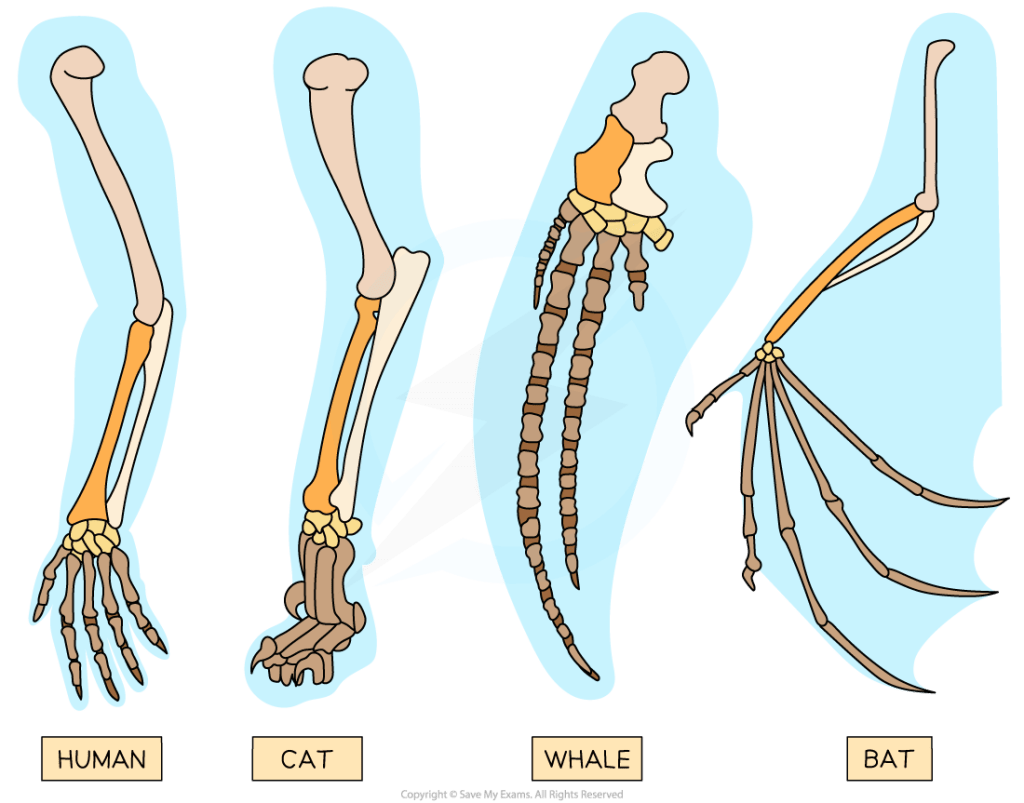

When organisms share similar internal layouts, even when those parts serve different functions, it points to inheritance from a common ancestor followed by gradual modification over time.

One of the clearest examples is seen in homologous structures—body parts that share the same basic design across species despite being used in different ways. The familiar five-digit limb found in humans, whales, bats, and dogs illustrates this well. Although a whale uses its flipper for swimming and a bat uses its wing for flight, both are built from the same underlying bones arranged in the same order. This shared structure is best explained by common ancestry rather than independent creation.9

Not all similarities reflect shared ancestry. Some arise because different organisms face similar challenges. Sharks and dolphins, for example, both have streamlined bodies and fins suited for life in water, yet one is a fish and the other a mammal. These analogous structures are the result of convergent evolution, showing how natural selection can produce similar solutions in unrelated lineages.10

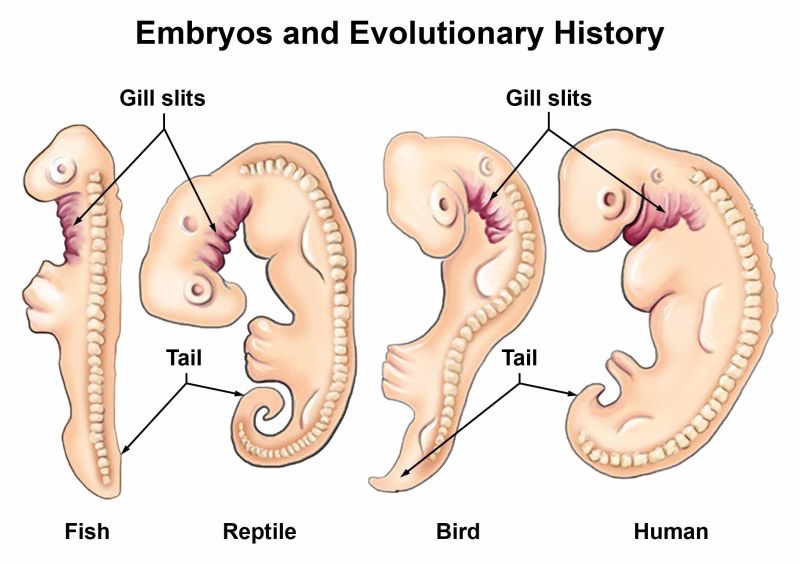

Evolutionary history is also preserved in vestigial structures, such as the pelvic bones found in whales and snakes or the human tailbone, which point to fully functional structures in distant ancestors. Further evidence comes from comparative embryology: many vertebrates look nearly identical during early development, often possessing features like “gill slits” and tails, reflecting their shared ancestry before their embryonic development follows diverging paths.11

The Genetic Record of Evolution

All known living organisms—from bacteria to humans—use the same genetic code to translate DNA into proteins. This shared system is one of the strongest indicators of common ancestry, suggesting that it originated once in an early form of life and has been passed down, with modifications, ever since.

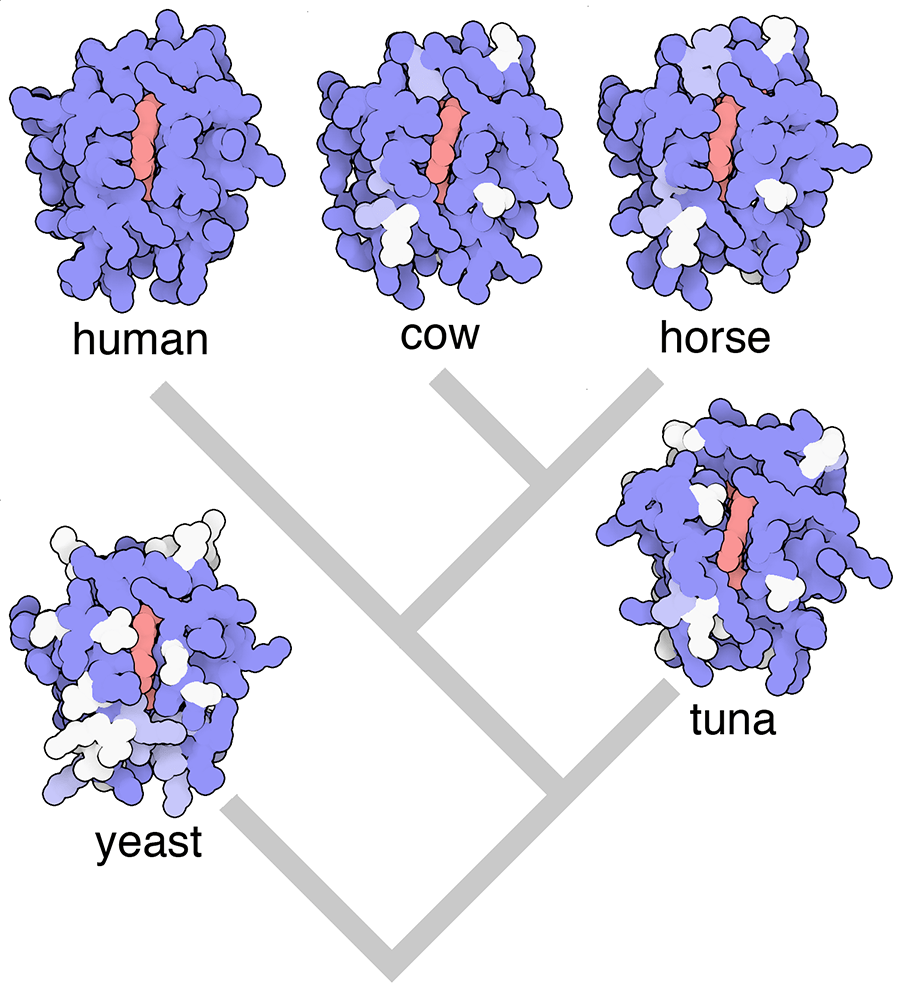

By comparing DNA sequences or the amino acid sequences of proteins, we can measure how closely related different species are. The more similar the sequences, the more recently two species shared a common ancestor. A well-studied example is cytochrome c, a protein involved in cellular energy production. Its structure is nearly identical in humans and chimpanzees, but shows increasing differences when compared to more distant relatives such as horses or yeast—forming a molecular family tree that mirrors what we see in fossils and anatomy.12

Genomes also preserve what can be thought of as molecular fossils. Pseudogenes are broken or inactive copies of genes that once functioned in an ancestor. Humans, for instance, carry a disabled gene for producing vitamin C, which remains functional in most other mammals, marking a shared loss in our primate lineage.13 Endogenous retroviruses tell a similar story: these are remnants of ancient viral infections that became permanently embedded in DNA. Humans and chimpanzees share many of these viral sequences in the exact same genomic locations, a pattern that is best explained by inheritance from a common ancestor rather than coincidence.14

Life Shaped by Geography

Biogeography is the study of how species are distributed across the planet and how they came to live where they do over time. Rather than being random, these patterns closely track common ancestry, migration, and the slow movement of Earth’s continents.

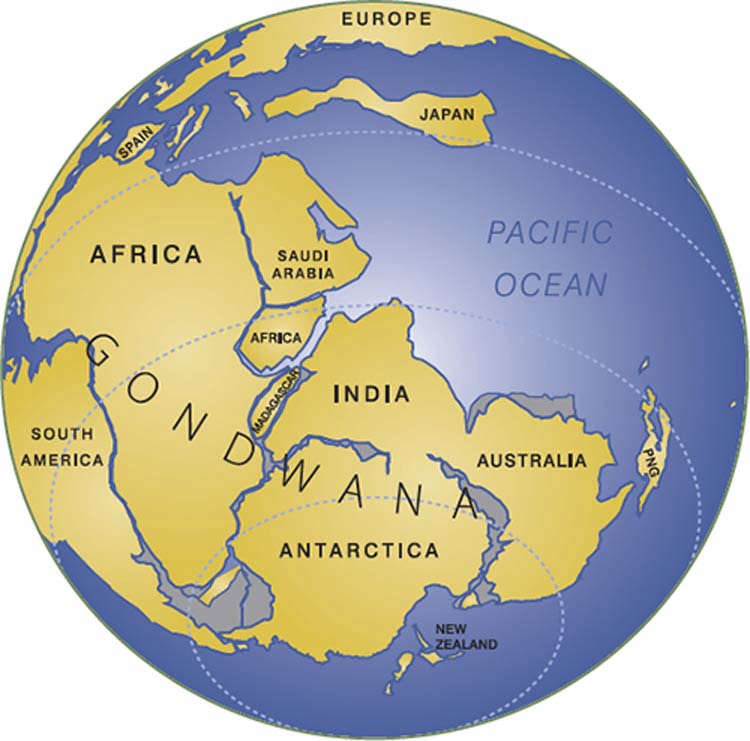

The shifting arrangement of continents helps explain why closely related species are often found on landmasses now separated by vast oceans. Marsupials, for example, are concentrated in Australia and parts of South America. These continents, along with Antarctica, were once connected as the supercontinent Gondwana, allowing early marsupial ancestors to spread freely before the landmasses gradually drifted apart.15

Islands act as natural experiments in evolution. Because they are isolated, species that arrive there often diversify into many distinct forms. Darwin famously observed this in the Galápagos Islands, where finches and tortoises closely resemble species from nearby South America rather than those found on distant islands with similar climates. The resemblance reflects shared ancestry, while the differences reflect adaptation after isolation.16

Evolution also makes clear predictions about where organisms should not be found. Large land mammals that cannot cross oceans are absent from remote islands such as Hawaii and New Zealand, where the only native mammals were bats and seals.

The same principle explains why polar bears are found only in the Arctic and penguins only in the Southern Hemisphere. Although both regions offer similar icy environments, each species remains confined to the part of the world where its ancestors evolved. These patterns make sense if species spread, became isolated, and changed over time—but are difficult to explain if organisms were simply placed wherever conditions happened to be suitable.

Evolution in Real Time

In organisms that reproduce rapidly, evolution can be watched as it happens. Since 1988, Richard Lenski’s Long-Term Evolution Experiment has followed E. coli through more than 80,000 generations. Along the way, one population evolved the ability to metabolize citrate—a nutrient that E. coli had been physically unable to use before.17

This was not a minor tweak, but the opening of an entirely new food source, achieved through ordinary mutation and natural selection. In evolutionary terms, it is the same kind of change that allows a population to exploit a new environment, spread into new territory, or eventually diverge into something recognizably new. Evolution here is not assumed—it is directly observed, generation by generation.

Where Does This Leave Us?

During my junior year at the University of Alabama, I worked on machine learning research and watched successive generations of a program learn to recognize handwritten numbers. What began as random guesses gradually improved through a simple process resembling natural selection. Though artificial, the result was unmistakable: complexity and apparent intelligence emerged from cumulative change.

Biological evolution follows the same logic, but on a vastly longer timescale. Over billions of years, small differences accumulate, building the diversity and complexity of life we see today. Our planet, this tiny pale blue dot, has existed for nearly 4.6 billion years—about one-third as old as the universe itself—providing an almost unimaginable span of time for life to arise and transform.

Even in the face of overwhelming evidence, some worry that evolution diminishes our humanity, as though natural origins make us less special. I find the opposite to be true. To understand that the atoms in our bodies were forged in ancient stars, and that we are the product of an unbroken chain of life stretching back to the earliest replicators, only deepens my sense of wonder.

We are not separate from the universe that made us. We are shaped by it, composed of it, and now conscious enough to reflect on our own beginnings. In that awareness, evolution does not reduce us—it reveals just how extraordinary the journey has been.

Sources

- Brenan, M. (2025, March 18). Majority still credits god for humankind, but not creationism. Gallup.com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/647594/majority-credits-god-humankind-not-creationism.aspx

↩︎ - Age of the Earth. Geologic Time: Age of the Earth. (n.d.). https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/geotime/age.html

↩︎ - Dawkins, R. (2016). The selfish gene: 40th anniversary edition. Oxford University Press.

↩︎ - Ohtomo, Y., Kakegawa, T., Ishida, A., Nagase, T., & Rosing, M. T. (2013, December 8). Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks. Nature News. https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo2025#citeas

↩︎ - Schirrmeister, B. E., de Vos, J. M., Antonelli, A., & Bagheri, H. C. (2013, January 29). Evolution of multicellularity coincided with increased diversification of cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation event. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3562814/

↩︎ - The age of the oldest tetrapod tracks from Zachełmie, Poland. (n.d.). https://www.scup.com/doi/10.1111/let.12083

↩︎ - Vidal, C. M., Lane, C. S., Asrat, A., Barfod, D. N., Mark, D. F., Tomlinson, E. L., Tadesse, A. Z., Yirgu, G., Deino, A., Hutchison, W., Mounier, A., & Oppenheimer, C. (2022, January). Age of the oldest known homo sapiens from Eastern Africa. Nature. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8791829/

↩︎ - MacRae, A. (n.d.). Radiometric Dating and the Geological Time Scale. Radiometric dating and the geological time scale. https://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/dating.html

↩︎ - Examples of Homology. Understanding Evolution. (n.d.). https://evolution.berkeley.edu/examples-of-homology/legs-and-limbs/

↩︎ - Similarities and differences: Understanding homology and convergent evolution. (n.d.-a). https://evolution.berkeley.edu/teach-resources/similarities-and-differences-understanding-homology-and-analogy/

↩︎ - Hall, B. K. (1999). Evolutionary Developmental Biology. Springer Netherlands.

↩︎ - Lomax, M. I., Hewett-Emmett, D., Yang, T. L., & Grossman, L. I. (1992, June 15). Rapid evolution of the human gene for cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC49272/

↩︎ - H;, Y. (n.d.). Conserved or lost: Molecular evolution of the key gene gulo in vertebrate vitamin C biosynthesis. Biochemical genetics. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23404229/

↩︎ - Belshaw, R., Pereira, V., Katzourakis, A., Talbot, G., Paces, J., Burt, A., & Tristem, M. (2004, April 6). Long-term reinfection of the human genome by endogenous retroviruses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC387345/

↩︎ - Nilsson, M. A., Churakov, G., Sommer, M., Tran, N. V., Zemann, A., Brosius, J., & Schmitz, J. (2010, July 27). Tracking marsupial evolution using archaic genomic retroposon insertions. PLoS biology. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2910653/

↩︎ - Darwin, C. (2009). The origin of species: By means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. Cambridge University Press.

↩︎ - Blount, Z. D., Borland, C. Z., & Lenski, R. E. (2008, June 10). Historical contingency and the evolution of a key innovation in an experimental population of escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2430337/

↩︎